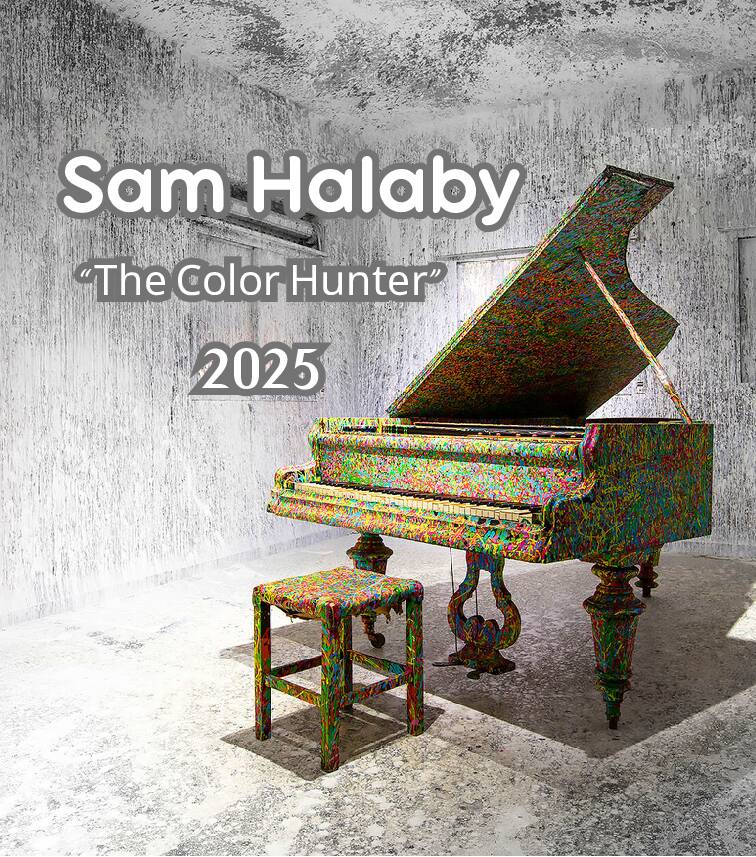

The international Druze artist, Sam Halaby, presents for the first time his exhibition “The Color Hunter” at CONTEXT Art Miami in the United States, represented by “Tribes Art Gallery”, during the most important week of contemporary art in America, December 2–7, 2025.

CONTEXT Art Miami is an art fair that creates a meaningful dialogue between artists, galleries, and collectors, offering the ultimate platform for showcasing groundbreaking talent. The collaborative efforts of CONTEXT Art Miami provide a unique and alternative opportunity for leading artists to gain international exposure and promote their work during the most significant week for contemporary art in America.

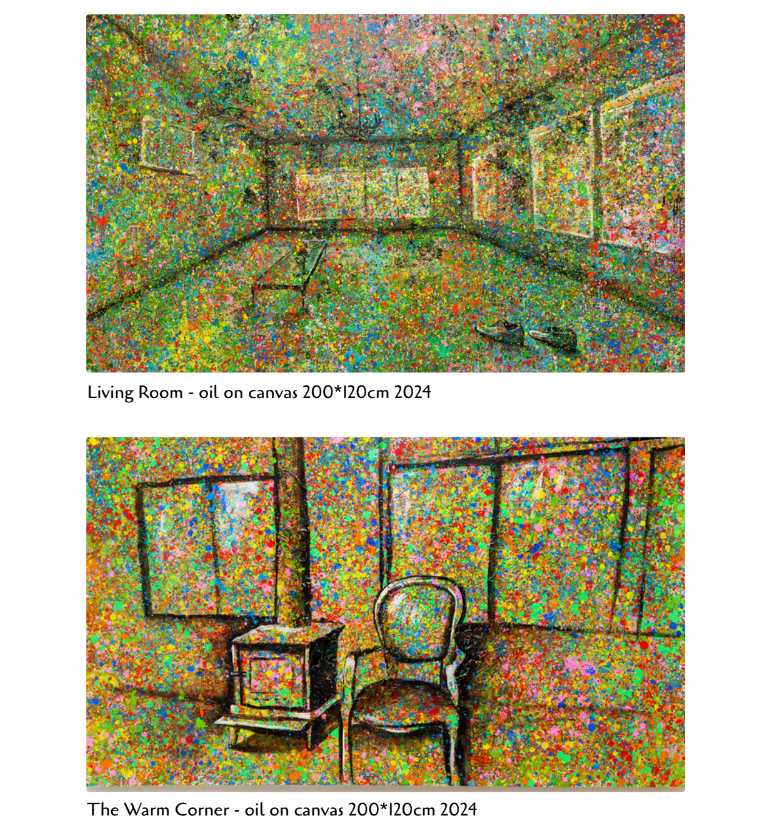

“The Color Hunter”- Sam Halaby’s new exhibition in Miami- unfolds as a multilayered visual journey reflecting the artist’s spiritual migration between worlds of light and shadow, joy and contemplation. His works, selected from various creative periods, reveal an ongoing dialogue between the vibrant and explosive color and the quiet power of black and white, those moments when silence speaks aloud. Halaby invites the viewer to wander among dozens of canvases as if traversing states of consciousness, discovering in every brushstroke the desire to paint reality anew – not merely as it appears, but as it is experienced. This is an exhibition where color becomes language, form becomes emotion, and art transforms into a window of social, cultural, and personal depth.

Visitors are invited to experience Sam Halaby’s exhibition – an artist who colors our world with positive energy, and to participate in the interactive art installation “Coloring Our Lives,” during which the artist invites the audience to literally step into his colorful world and be painted in dozens of shades representing optimism, hope, love, and innocence. Many public figures around the world – mayors, singers, artists, and the general public have already joined this unique participatory artwork.

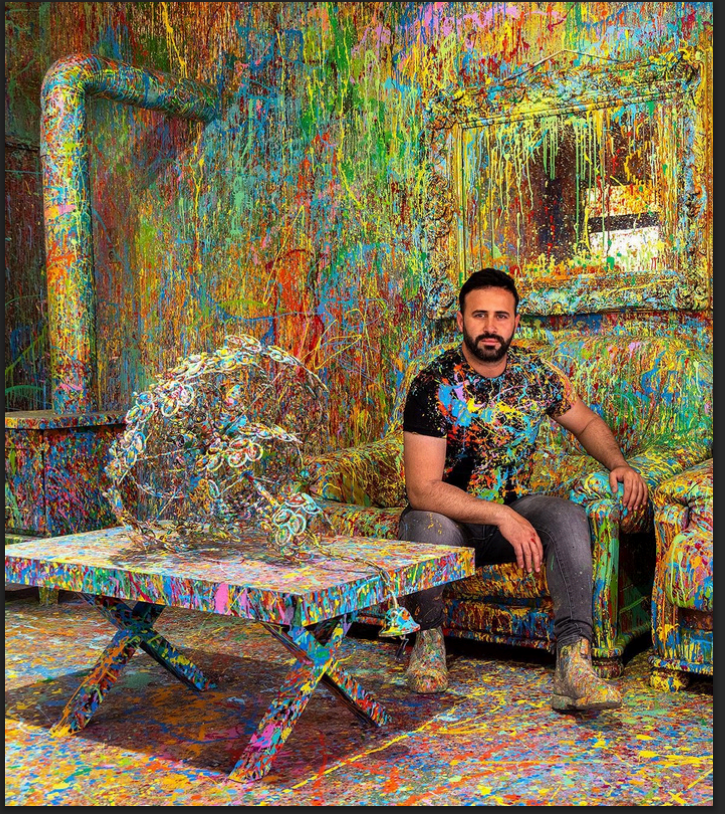

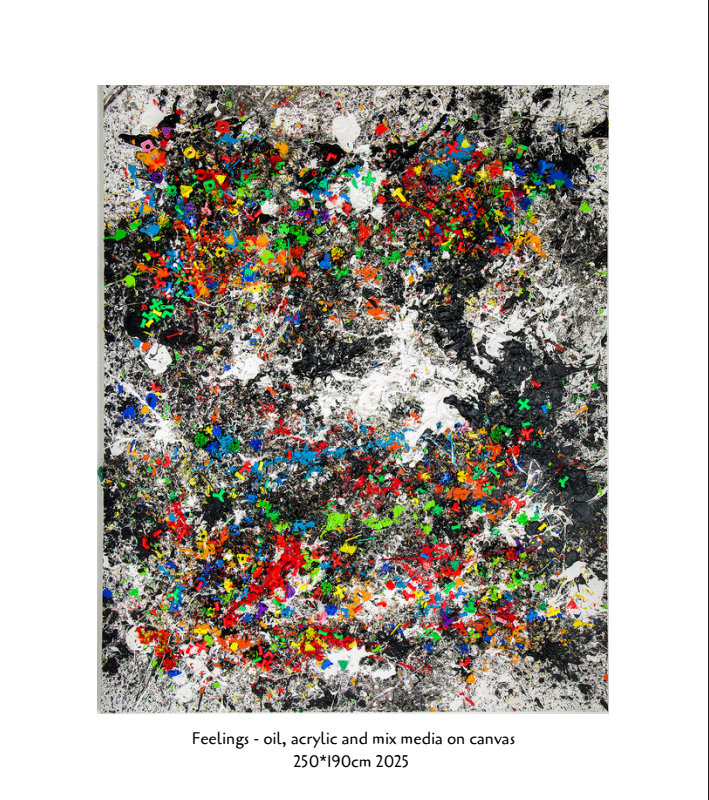

Sam Halaby paints in thousands of shades, creating with intensity and a kind of magical power in his bold splashes of color, which he spreads from his brush onto large canvases and the walls of his own home. His technique can be defined as a massive, forceful dripping style that forms a new, previously unseen texture on the surface.

Halaby’s work may, in certain aspects, be compared, though inherently different to that of the renowned American artist Jackson Pollock. Pollock, who created the “drip painting” technique in the 1940s, used liquid paints on canvases laid on the floor, which he dripped and splattered. He viewed dripping as a direct expression of consciousness and the subconscious a dance of painting in motion, also known as “action art.”

Halaby brings a fresh and youthful spirit to a new generation of audiences, many from the worlds of hi-tech and business. Among his collectors are leading figures in the art world. His active, expansive studio is located in the heart of the village of Daliyat al-Karmel, surrounded by shops and artistic attractions. By placing his studio in such a dynamic urban center, Halaby makes a clear statement to his surroundings: “Here I am, among you.”

Over time, he expanded part of his activity to “The Color House” – a new artistic space that serves as both cultural preservation and a subtle protest against exclusion and marginalization. The home environment has become a stage for aesthetic and artistic creation. The Color House has become an international cultural attraction, drawing over one million visitors in the past two years and reaching hundreds of millions on social media worldwide.

The transformation of Halaby’s family home into a work of art echoes the legacy of classical artist Claude Monet, who turned his home in Giverny, France, into a living artwork that combined painting, gardening, and natural color harmony. Similarly, Halaby realizes a total artistic vision, where the domestic space is not merely a backdrop but the artwork itself , a concept historically defined as “Gesamtkunstwerk.”

Halaby’s choice to revive his home through vivid colors, recycled objects, symbolic imagery, and a folk-inspired personal visual language reflects a profound cultural identity. As a member of the Druze community – an ethnic minority within a diverse society, he navigates the tension between tradition and innovation, between periphery and center, between individual and collective identity.

Each room in The Color House represents a chapter of memory from Halaby’s personal life. The spirit of his parents and sisters flows through the vibrant house. The living room and family space retain their original furniture, now coated in dazzling hues. The kitchen has become an exhibition of limitless colors, and Halaby’s childhood room evokes empathy and emotional connection from visitors.

A special room is dedicated to his late mother, to whom he was deeply connected. Halaby paints on her original scarves – a moving artistic act blending the personal, cultural, and aesthetic. As a boy, Sam accompanied his mother to the village market, where she sold her hand-designed scarves. The scarf – an intimate, feminine object associated with Druze tradition, gains new meaning as it becomes a painted canvas. This act serves as both homage and reinterpretation – a gesture of tenderness, identity, and reconciliation. Through color the core of his artistic language, Halaby breathes new life into the fabric, bridging memory, gender, and creativity.

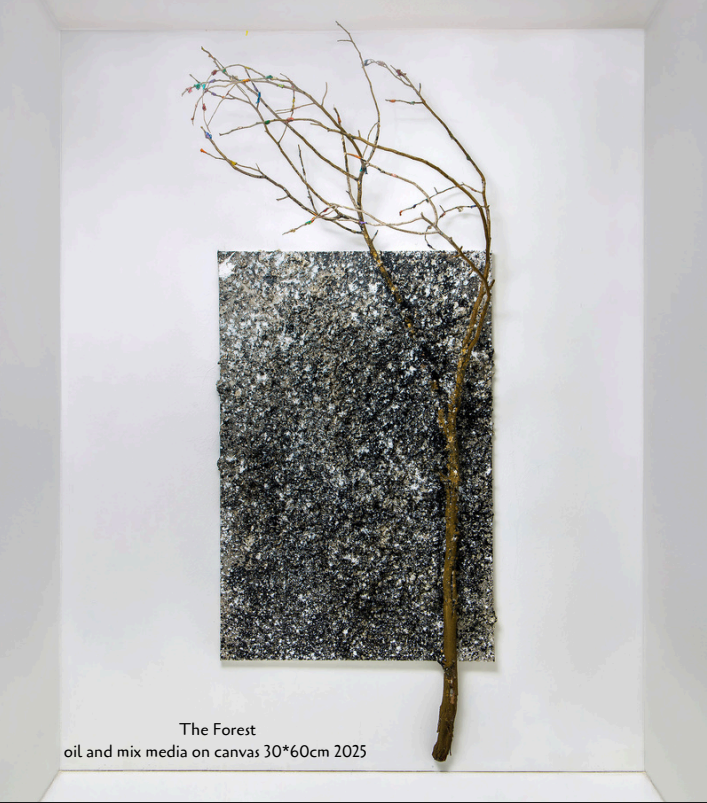

In recent years, Halaby has been invited to design architectural, commercial, and public spaces in major shopping centers throughout Israel. Shoppers are invited to stroll through newly created, colorful environments – artificial nature bursting with vivid sculptures and fantasy-like trees reminiscent of Shakespeare’s enchanted forests. His art is marked by conceptual and visual duality, evident even in his early tree paintings, many of which were two-dimensional reliefs in rich pop-art style.

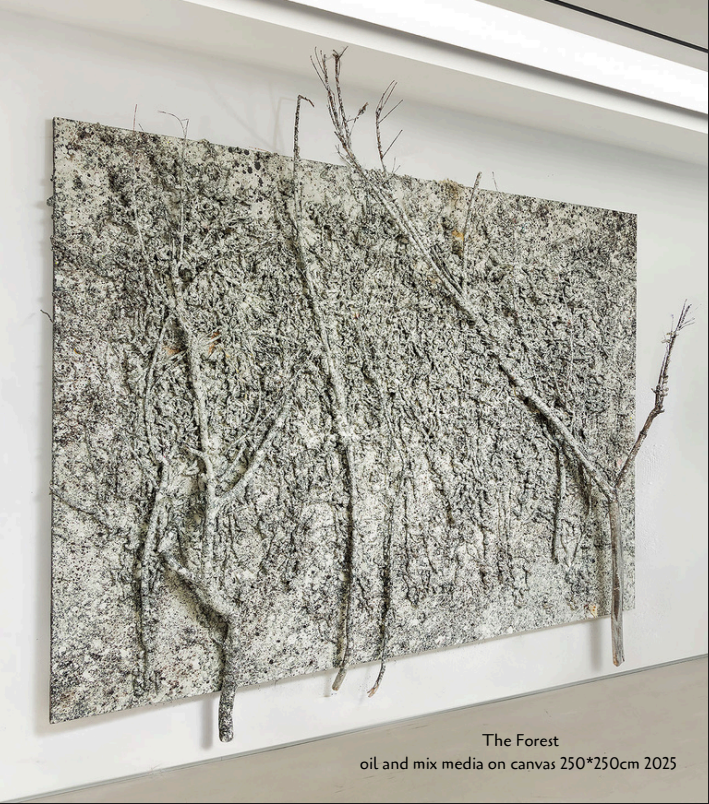

Today, Halaby also paints conceptual black-and-white trees – a key element for understanding his visual language and the deep social, cultural, and personal meanings embedded within. His latest series of abstract, energetic paintings continues this artistic statement. These works, often rendered in powerful drips and splashes of black, gray, and blue, immerse the viewer in dramatic and emotional worlds.

The colorful trees and flowers symbolize vitality, growth, and renewal, while also reflecting Halaby’s inner vision. As the tenth child , following nine sisters , he expresses his unique identity as the independent, creative son who brings freshness and innovation to his family and community. His connection to nature and the Carmel landscape of his childhood serves as a metaphor for hope and spiritual search. Conversely, his black-and-white trees represent memory, complexity, and sometimes alienation – even social critique, hinting at a world divided and monochrome. Through this interplay of vivid and monochromatic expression, Halaby creates a dialogue between past and present, individual and collective identity, and between hope and a challenging reality.

As part of his ongoing creative evolution, Halaby also transformed a real, functioning car into a mobile artwork – a colorful, moving installation that astonishes all who see it. With humor and brilliance, he spreads joy and positive energy through vibrant colors that seem to heal the environment. The car covered in thousands of dripped shades has become a unique attraction in the rural landscape of Daliyat al-Karmel.

This project, which turns a moving vehicle into a dynamic work of art, joins a long artistic tradition of using cars as cultural objects, not only as transportation but as symbols of personal expression. Halaby recently designed a unique Mercedes vehicle in his signature style, a collaboration that became a celebrated success and injected youthful, colorful energy into the brand’s Israeli offices.

The Color Hunter Exhibition Opening Hours:

Tuesday, December 2 – 16:00 to 21:00

Wednesday, December 3 – 11:00 to 19:00

Thursday, December 4 – 11:00 to 19:00

Friday, December 5 – 11:00 to 19:00

Saturday, December 6 – 11:00 to 19:00

Sunday, December 7 – 11:00 to 18:00

Ticket link: https://www.contextartmiami.com/tickets

Video link: https://youtube.com/shorts/R0wjRlYqR9A?si=8gIjYixppjn_dO7c

Location: The CONTEXT Art Miami Pavilion One Herald Plaza @ NE 14th Street | Downtown Miami On Biscayne Bay between the Venetian & MacArthur Causeways Tribes Art Gallery – Booth A26

Sam Halaby – Digital Assets:

https://samhalaby.com/

https://youtube.com/@samhalaby?si=R4EAlfJ1u92YW1uh

https://www.instagram.com/_sam_halaby/profilecard/?igsh=cG5nejF2MHgzdHV4

https://www.tiktok.com/@artist.sam.halaby?_t=8sS4Jwn55VK&_r=1

For additional information and interview coordination: Sigal Feldman – Public Relations & Management

+972-52-233-1748 | sigal@sigalfeldmanpr.com